Hallowed Halls

Sep 11, 2025; From the Bowels of the Langseth (i.e., the “Main Lab”)

Dear Readers,

We’re now well into our transit, and at the time of writing, have just left Mexico’s exclusive economic zone. Many of our science operations have now begun in earnest, including (1) the use of eXpendable BathyThermographs (XBTs) to probe the properties of the water column and (2) the collection of multibeam data, which provides estimates of seafloor bathymetry. It’s an exciting time! The science party has settled into something of a cozy rhythm, with regular training on science operations punctuated by science presentations, occasional sonar chirps, and discussions of literature germane to mid-ocean ridge dynamics. Meanwhile, half of us are steadily preparing to offset our sleep schedules, girding ourselves for the coveted night shifts that take place during the OBS deployment phase of our expedition.

As we’ve acclimated more to life onboard a vessel (and now that I’ve gotten comfortable navigating the ship without getting lost) I’ve had the privilege of being able to spend more time appreciating the R.V. Marcus Langseth, our home for the next month. As I walk these swaying corridors, I constantly come across little reminders of how special this vessel is, even among the diverse U.S. academic research fleet. I wanted to share some of this appreciation with all of you.

The Langseth fills a unique niche; it’s currently the only vessel operated by the U.S. academic research community with active-source capabilities and the ability to acquire 3-D multichannel seismic data (recording signals at multiple groups of receivers simultaneously) and conduct both 3-D seismic surveys and extended offset 2-D surveys (resolving deep structure, sometimes approaching 20-30 km) with its robust linear source array of 40 air guns (sources of compressed air). This unique and enduring capability is a testament to our fundamental scientific and industry need for high-resolution exploration and imaging of the oceans and seafloor, which is critical for understanding geohazards, energy, and climate change.

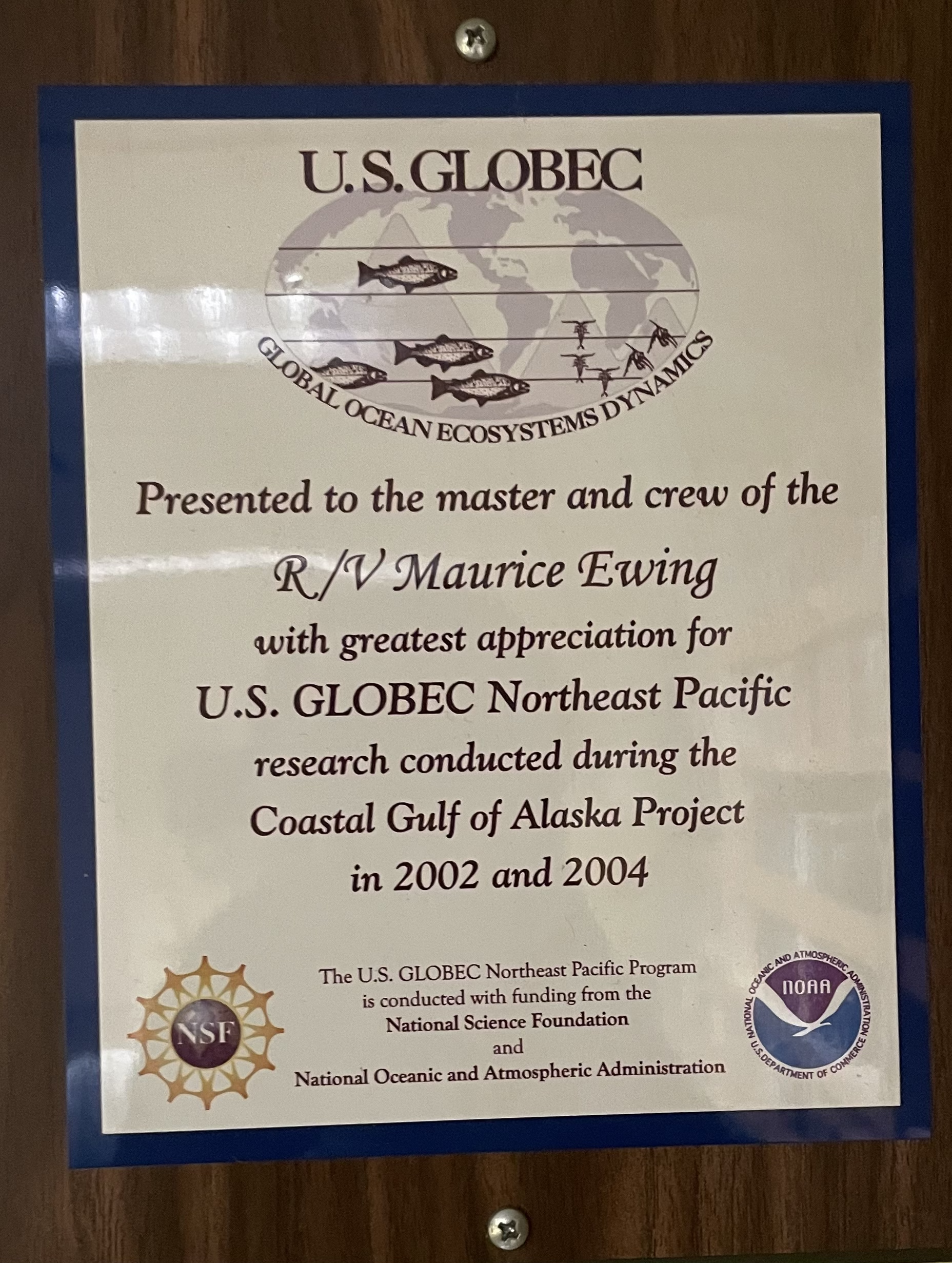

LDEO (the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory) has long led the operation of such research vessels, one of which was the Langseth’s predecessor, the R.V. Maurice Ewing (named after the pioneering oceanographer and founder of the then-named Lamont Geological Observatory). The Ewing, which operated between 1988-2005, (and before that, was owned by the Canadian Crown Corporation, Petro-Canada) was initially purchased by the Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory of Columbia University and later owned by the National Science Foundation. The Maurice Ewing served the then-burgeoning marine geophysics community through a myriad of investigations, deploying ~20,000 miles of multichannel seismic profiles across the world and vastly improving our understanding of crustal accretion processes at mid-ocean ridges, subduction zone tectonics, and the global distribution of marine gas hydrate deposits, as well as supporting some oceanographic endeavors.

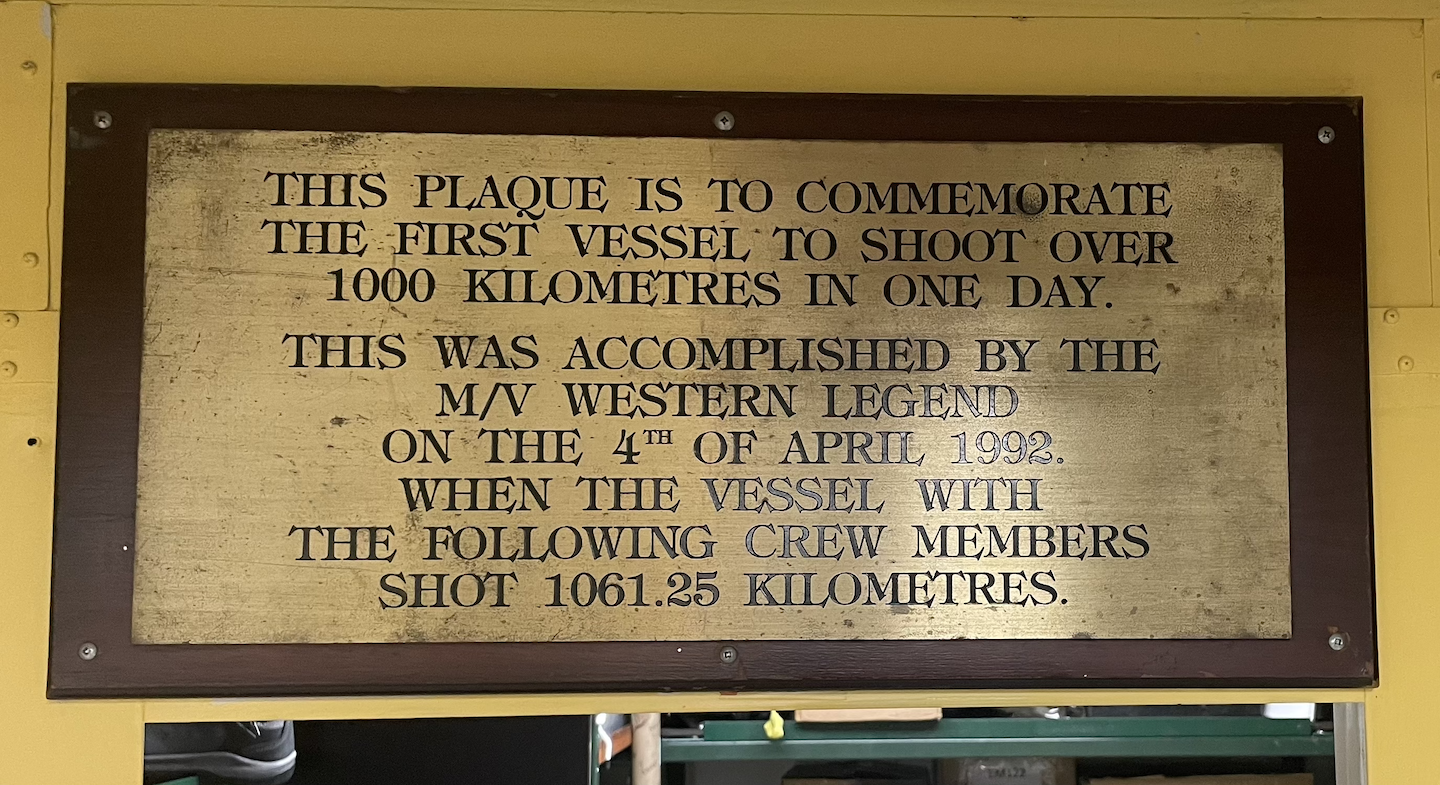

However, as the marine geophysics community grew and the scope of its endeavors expanded, the global scientific community’s science needs began to exceed what the Ewing could provide. The Ewing could only tow single seismic source and receiver arrays; higher-resolution experiments and imaging demanded more precise mapping of swaths of deepwater regions, the ability to deploy multiple airgun sources, and the space and facilities to recover and shoot sources to large arrays of OBSs (ocean-bottom seismometers). This led to the Ewing’s retirement in 2005; however, as one door closes, another opens, and just as the Ewing was once an industry seismic vessel, so was the Langseth. LDEO soon purchased a used industry vessel, the Western Legend, from Western Geco Inc; the Legend was then refit for both seismic and oceanographic capabilities and, as the R.V. Marcus Langseth, began serving as the premier marine geosciences research vessel. In late 2007, the Langseth’s title was turned over to the NSF; since then, it has embarked on a variety of expeditions that have changed our understanding of marine subsurface structure.

In 2008, the academic marine geophysics community used the Langseth to break new frontiers and acquire the first 3D seismic dataset outside of industry, yielding exquisite constraints on the dynamics of an active portion of the East Pacific Rise. The Langseth has since continued to conduct experiments at sites from Costa Rica to Taiwan, and diverse tectonic environments from oceanic plateaus to the subduction zones. Science targets have included high-resolution imaging of subduction zone structure to understand the dynamics underpinning hazardous ruptures, mapping stratigraphy at volcanic rifted margins, probing the stratigraphic record at sedimentary basins to study changes in sea level, and accurately assessing gas hydrate concentrations.

However, all has not been perfect for this community. The logistically complex nature of the work the Langseth performs has necessitated caution, and sometimes, unexpected challenges; in 2009, the vessel was barred from performing active imaging in the Taiwan Strait, and also faced challenges from lawsuits alleging that the ship’s activities would threaten marine life off the coast of British Columbia. Furthermore, high operations costs place pressure on the vessel, and in Fall 2017, NSF sought proposals to explore alternate avenues for the marine geophysics’ ability to access similar seismic infrastructure provided by the Langseth; in 2020, it was announced that the Langseth would move under the ownership of LDEO, while still supported by the NSF.

To this day, work continues to understand how the Langseth and other vessels can best serve the marine geophysics community’s needs, but what is certain to me, as I look around a room filled with plaques commemorating the achievements of the Langseth and preceding vessels, is that there truly is no vessel quite like this. The science community has benefited immeasurably from the data and facilities provided by the Langseth and its stewards, and I, for one, feel incredibly fortunate to be able to sail on it.

Signing off, -Anant Hariharan.